In 1943, in the midst of the Second World War, General Matthew Ridgway went toe-to-toe with then-General Dwight Eisenhower to oppose Giant II, a planned military operation. Ridgway believed the plan could be a mistake, made that opinion known to the point of near insubordination, and turned out to be right.

As a result, he saved the lives of thousands of American soldiers in the 82nd Airborne Division.

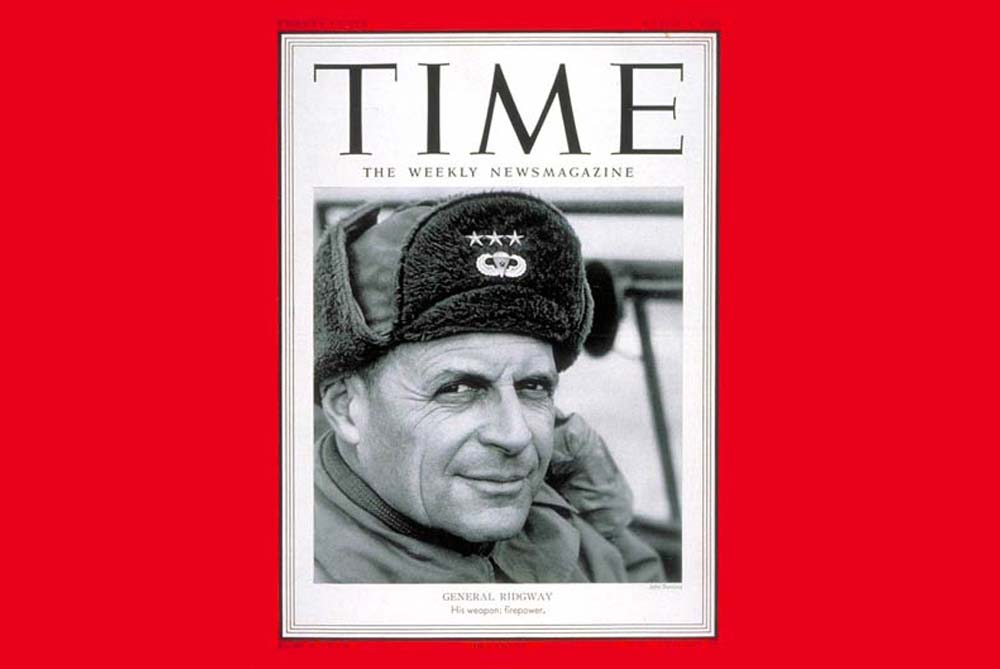

Ridgway is not a name that is widely known, despite his long service and influence on United States political policy. History shows him to be a leader who wasn’t afraid to challenge popular opinion if he recognized a potential flaw in the thinking. Though obviously just one of many decisions Ridgway made across an extensive military career, his opposition to Giant II provides a compelling example of what it means to be a courageous leader.

Several recent incidents have highlighted failings in courage among those we consider “leaders.” These are the stories where, looking back on the situation, someone in a leadership role says, “Yes, we knew there were some issues and someone should have taken action or spoken up.”

“Someone?” Why not you?

A lot is written about the characteristics of great leaders, and one that always stands out is their willingness to make and stand behind a potentially unpopular decision. Indeed, sometimes it is a single decision that causes history to remember someone as a great leader. Rather than falling victim to groupthink, the individual will step forward and say, “Can we analyze this from a different angle before we act?”

Making such a statement can require tremendous courage where it challenges what everyone else has accepted as “the conclusion.” Asking a group to go backwards and re-examine the facts and reasoning that led to “the conclusion” can be frustrating to those who “don’t want to go over all of this again” because “we just want to get past this.” But sometimes using a different lens, or testing those “facts” and reasoning, can result in a completely different perspective.

The United States had signed a secret peace agreement with Italy in September, 1943. Benito Mussolini had been temporarily removed from power, and the new Prime Minister, Pietro Badoglio, started secret negotiations with the United States to end the war for Italy. The Allied military leadership, in collaboration with Italy, had a plan to capture Rome and expel the Germans. It was a surprise attack. The 82nd Airborne Division would parachute outside of Rome on September 8, link up with Italian forces, and march on Rome, driving the German troops into the mountains north of the city. The plan, called Giant II, seemed an act of genius.

Ridgway, commander of the 82nd Airborne, felt the plan too risky to commit his people. He said he would not support it. In the military, where the culture is to follow orders, Ridgway was taking a big risk. He was essentially telling his boss, Dwight Eisenhower, “I disagree with the plan and will not follow orders.”

Eisenhower agreed to pursue more information on the situation with the Italians before moving forward. Two Allied military officers slipped into Northern Italy and met with the Italian leadership. They discovered two things: first, the Italians planned to back out of the attack, leaving the American soldiers exposed to the existing German forces; and second, those German forces were much greater than what Eisenhower had been told. The 3,000 American paratroopers had already started to take off for Italy. They would be facing 24,000 German soldiers and 150 tanks. Ridgeway’s soldiers were heading for a massacre.

Frantic communications caused the planes to turn around. The entire mission was canceled.

Ridgway was promoted to several positions of leadership during the Korean War and ultimately became Chief of Staff of the United States Army under President Eisenhower.

During the growing conflict in Vietnam, the United States military proposed Operation Vulture to bolster the French and make the United States a party in the war with the use of tactical nuclear weapons. Vice-President Richard Nixon, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chair Arthur Radford supported the plan. Eisenhower asked Ridgway his opinion. Ridgway analyzed the situation and said not to move forward. The plan was scrapped and Eisenhower withheld involvement by the United States in Vietnam for his 8 years in office.

The term “dissenting voice” is often used for the person who does not agree to go along with the pack. Leadership is about having the willingness to be that “dissenting voice” on the chance that you have identified something that was missed, or maybe the group has reached a faulty conclusion. In that, we all have the opportunity to be “leaders” where we might help colleagues or an organization make a better decision by suggesting a different point of view. Sometimes all it takes is a single question: “Is there something we may not have thought through or talked about. For example, what if…?”

Ridgway said he never regretted the decisions he made in his career. He died in 1993 at the age of 98. When he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, General Colin Powell gave the graveside eulogy and said, “No soldier ever performed his duty better than this man. No soldier ever upheld his honor better than this man. No soldier ever loved his country more than this man did. Every American soldier owes a debt to this great man.”